FOOD SECURITY AND INTERNATIONAL LAW:

The world’s population is projected to increase to 9.8 billion by 2050. However, 828 million people – close to 10% of the world’s population – still face hunger. The number of undernourished people grew by as many as 150 million. After steadily declining for a decade, world hunger is once again on the rise and SDG 2 (zero hunger) is unlikely to be met by 2030.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the acute problems of hunger and malnutrition. The Russia-Ukraine conflict has compounded this problem. Increasing occurrences of extreme climate events have disrupted global supply chains, further impeding progress towards food security, especially in low-income countries. With food and energy prices increasing, the situation in both developing and developed countries is fast deteriorating.

This alarming reality hides a complex paradox – there is more than enough food produced in the world to feed everyone on the planet, and yet 10% of the world population continues to suffer from hunger. Small farmers, herders, and fishermen who produce about 70% of the global food supply remain vulnerable to food insecurity. About 14 million children under the age of five suffer from acute malnutrition.

According to the FAO, “food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life”. A person is ‘food insecure’ when he lacks regular access to enough safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development– whether due to unavailability of food and/or lack of resources to obtain food.

While several instruments recognize and reiterate the right to food as a human right under international law, it is most comprehensively addressed under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). Article 11.1 of the ICESCR recognizes the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living, which includes access to “adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions”. The Declaration of Nyéléni, signed in 2007, introduced the concept of “food sovereignty”. Food sovereignty, according to the Declaration, is the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.

For countries working towards food security, food sovereignty requires utilizing state-of-the-art technologies, scientific knowledge of agricultural systems, and nutrition to improve the methods of production, conservation, and distribution of food. Agricultural innovation becomes imperative to increase productivity and security to the global food supply. For instance, farm automation, including automated harvesters, drones, autonomous tractors, seeding, and weeding can help bring together agricultural machinery, computer systems, electronics, chemical sensors, and data management to reduce labour time, promote higher yields, and efficient use of resources. Similarly, indoor vertical farming, through hydroponics or aeroponics, enables producers to get healthier and bigger yields by controlling variables such as light, temperature, water, and sometimes, carbon dioxide levels.

It is vital to develop sustainable, inclusive, healthy and resilient food systems. Technologies must be developed to reduce the environmental and climate impact of the production, aggregation, processing, distribution, consumption and disposal of food, forestry and fishery products. It is important to build resilience in production and supply chains to increase agricultural productivity. Food systems must be climate-friendly and reduce Green House Gases. Policy action in this area can help prevent food loss and control food waste. A global food system that is more productive, more inclusive of poor and marginalized populations, environmentally sustainable and resilient, and able to deliver healthy and nutritious diets to all is critical to realising the goal of food security.

Modern trade agreements have attempted to further this cause through dedicated chapters on the promotion of sustainable food systems. At the WTO, the importance of this objective was highlighted in the Twelfth Ministerial Conference in Geneva with the Ministerial Declaration on Responding to Modern Sanitary and Phytosanitary Challenges. The Declaration highlighted the importance of the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures in supporting sustainable agricultural growth and agricultural practices that aid in addressing climate change and global food insecurity.

Aside from agriculture, it is equally important to promote ‘Blue Economy’ and transition to sustainable fishing practices, which protect ocean health and marine ecosystems against threats such as acidification, pollution, ocean warming, eutrophication and fishery collapse. Countries must work towards sustainable management of ocean resources, carbon sequestration, coastal protection, and waste disposal to realise SDG 14 relating to conservation and sustainable use of the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development.

While sound policy making is critical in achieving these goals at the national level, international economic law can help in establishing a legal framework for trade that prioritises food security and work towards improving, not only food production and access where it is scarce, but also improving economic as well as sustainable access to food by creating jobs, raising income and ensuring the livelihood of farmers.

At the WTO, discussions on food security began in the early 2000s and became part of the 2001 Doha Ministerial Conference. The first significant breakthrough came during the 2013 Bali Ministerial Conference where Members adopted the Ministerial Decision on Public Stockholding for Food Security Purposes. Following the 2013 Bali Ministerial Conference, the 2015 Nairobi Ministerial Conference abolished agricultural export subsidies to prevent trade distortions in an effort to end hunger and achieve food security.

The Twelfth Ministerial Conference brought forth other important outcomes on food security and sustainable food practices. First, the Ministerial Declaration on the Emergency Response to Food Insecurity reinforced Members’ commitment to take concrete steps to improve the functioning and long-term resilience of global markets for food and agriculture. Second, the Ministerial Decision on the Exemption of WFP Food Purchases from Export Prohibitions or Restrictions requires Members to not impose export prohibitions or restrictions on foodstuffs purchased for non-commercial humanitarian purposes by the WFP in view of rising hunger levels. Third, the Ministerial Decision on the Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies represents a historic milestone in the promotion of sustainability by prohibiting harmful fisheries subsidies that have depleted the world’s fish stocks.

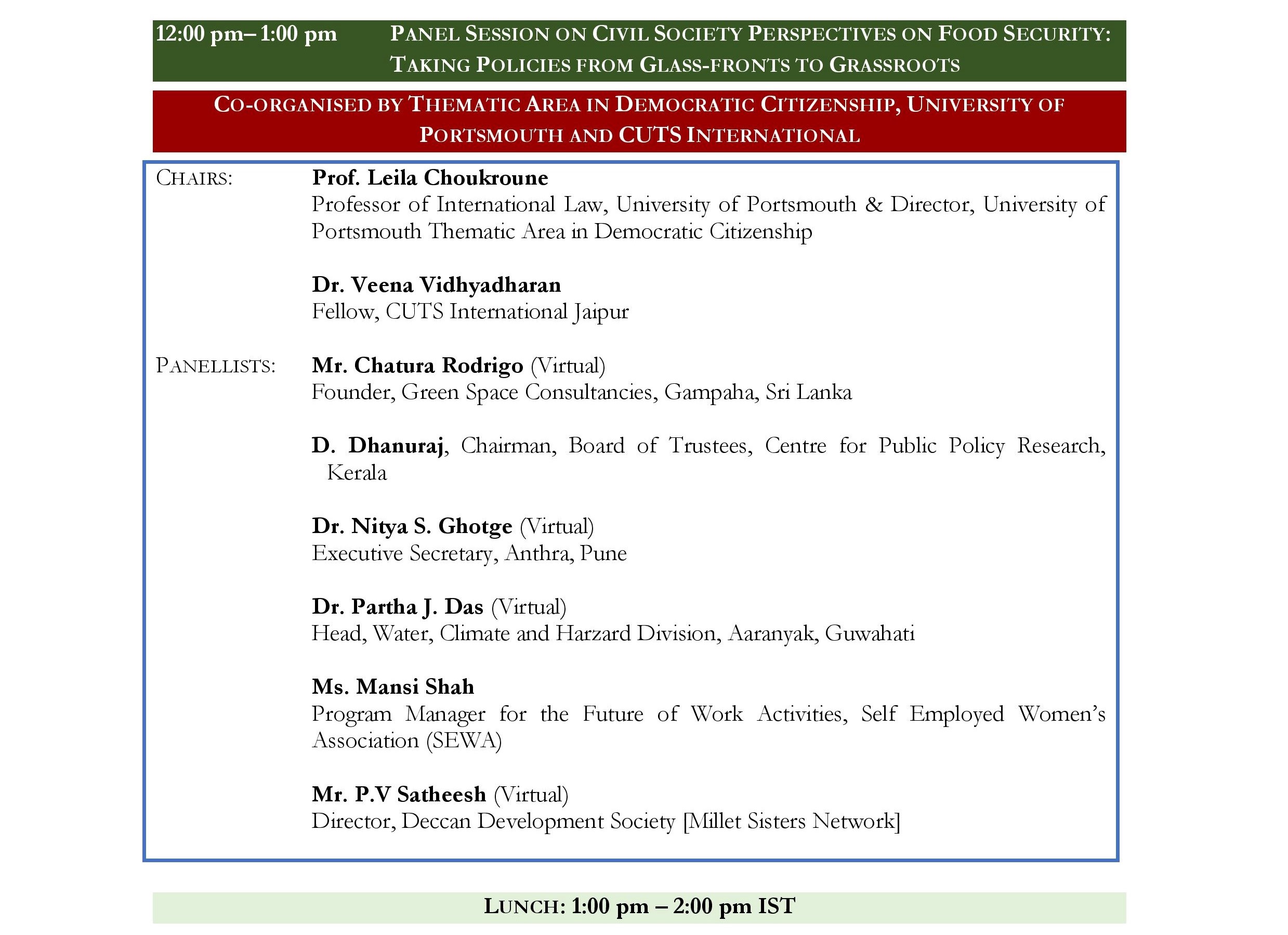

Several research papers that were selected from the SAIELN’s third Biennial Conference have been published in Volume 22, Issue 3 of Journal of International Trade Law and Policy. The publication highlights the significance and quality of the research presented at the conference, contributing to the ongoing scholarly discourse in the field of international law and policy.